If we allow our hearts to be broken they will be broken open not broken down, open to embrace everyone.

What I would like to share with you is something very simple but also very difficult: simple things often are. It is an invitation to pay the price for peace. We all know that peace is an exceedingly high good. But for an exceedingly high good we should expect to have to pay an exceedingly high price. I would like to explore with you what the price of peace is, and then to suggest why, in my opinion, the only force in human life that can generate enough energy to pay that price is religion. Obviously, to do this we will have to redefine religion a bit and look at what it is that makes religion religious, because it is by no means automatically religious. In fact, I tend to think it is automatically irreligious unless we do something to make it religious.

We are One and “They” Are “Us”

Let us first explore what price we have to pay for peace. I have four fairly simple points which you can augment or change, but which will give us a ground plan. First, it seems to me, we have to face our failure to create a peaceful world. The world around us is one we have all created together, and it is not a peaceful one. It costs us a great deal to admit that each one of us is implicated in having created this peace-less world. As long as we cannot admit this we are very far from peace, because we remain in a world in which there are “us” and “them”: “Us” the good ones and “them” the ones who present the problem and obstacle to peace, the enemy. It makes no difference who “they” are – they can be communists, the capitalists, the new age people, whoever. But if we face the fact that we are one, that “they” are “us”, that the face of the enemy is our own face, then we will have reached the first basis for peace.

I assure you this is terribly difficult. I talk so glibly about it here, but I find myself continuously sliding into, maybe not talking, but at least thinking about “they” – and if only “they” didn’t give us all that trouble we would have peace on Earth. So you have to think of something creative to bring home the fact that we are one. For example, just at the beginning of Lent one year, I found a photograph of some people who for me are “they”. That picture became my Lenten pin-up. I looked at it every day: “they” became “us”. So I suggest you think of something very creative that will bring home to you the fact that we are one: pick your “theys” and identify with them in some way or other.

Rise to Our Responsibility

Once we see it is we who have failed to make peace and we who can make peace, we obviously then have to rise to our responsibility and do something. The first thing most of us do is say, “What on earth can I do?” That’s great! You have marked out your homework. Find out: Ask that question. It’s much better than not to ask it. You see how far ahead we are if we ask what we can do for peace? Stick your head together with someone else asking the same question – as they say, two heads are better than one. If the two of you cannot come up with something, ask two others and suddenly there will be four people. Imagine the whole world sticking their heads together and asking what we can do – the solution would not be very far away.

The moment you ask the question, you will find things you can do. Very simple things. Some of you may know this story but I think it is worth repeating. About two years ago I was at the ordination of a Buddhist abbot. It was a very solemn occasion – incense, flowers, gold brocade, candles – and in the midst of the ceremony somebody’s beeper on their electronic wristwatch went off. Now you aren’t even supposed to wear a wristwatch in a zendo, so it was very embarrassing. Everybody was looking around: “Who is the poor guy to whom this has happened?” It turned out to be the abbot who was being ordained. He interrupted the whole ceremony and said, “This was no accident. I have set this alarm because I have made a vow that every day at 12 noon, regardless of what I am doing, I will stop and think thoughts of peace.” And he invited everybody there to think thoughts of peace with him for one minute.

Now we can all do something like that: set our little alarm-clocks, and if that interrupts a meeting say we’re terribly sorry, but we’ve made a vow to think thoughts of peace at that time. We could even get bells rung. For two years now a village on the south island of New Zealand has been ringing bells at 12 noon. Maybe you can find some little village or neighborhood where you can ring the bells, or a radio station that is willing to play beautiful bells for half a minute at 12 noon. Most local radio stations are looking for something interesting they can put on, so provide them with a half-minute tape of bells – something that will remind people over and over again. That’s one creative idea and you may have thousands of others.

As Marilyn Ferguson said so beautifully, depression is only sorrow that doesn’t go all the way to breaking our heart. But if we allow our hearts to be broken they will be broken open not broken down, open to embrace everyone.

We Are the Problem

Now, having faced the fact that we are one and having risen to our responsibility, we need to see that we are the problem. Not only in general but also specifically, in that most of us in the first world are exploiting the third world. So the third, very difficult, step is to give up some privilege we enjoy at the expense of others. For most of us, the willingness may be all we can muster to begin with. But we can be willing to make as a motto for ourselves what the first canonized saint of the United States, Mother Seton, said two hundred years ago: “Live simply so that others may simply live.”

Run the Risk

The fourth step is to run the risk involved in everything above. In the kind of world in which we live it is very risky to lead a moral life, because morality – and some people don’t like to hear this – is always unilateral. You do not make it a condition for your not stealing that others will not steal from you. You do not make it a condition that you will live a moral life provided others behave morally to you. We know it from our personal lives, but in public we always want bi-laterality. We do not want to be unilaterally honest or peaceful. That’s a great risk. If we dare to do it, it will cost us no less than everything. But it will be worth it. It will be a breaking of our heart. As Marilyn Ferguson said so beautifully, depression is only sorrow that doesn’t go all the way to breaking our heart. But if we allow our hearts to be broken they will be broken open not broken down, open to embrace everyone.

I have a small personal experience that fits in here. For a fairly long time I had continuous nose-bleeds which began to build up until at midnight mass last Christmas the whole thing came to a climax. We wear white at midnight mass, so a nose-bleed can be a big problem. It started just before we went in, and by the end of the ceremony I was a bloody mess. Afterwards I went to a friend in whom I have great confidence and he said, “I’ll pray with you about it, but first let’s examine what’s happening. I get the impression that you are quite exposed to a lot of things going on in the world. In other word, you are sticking your nose into a lot of things – and it breaks your heart. But you don’t allow your heart to bleed, and so your nose starts bleeding instead. Why don’t you unite your heart with the heart of Jesus and let it bleed, and then maybe your nose will stop bleeding.”

We live in a kind of world in which we need to let our hearts bleed.

Well, whenever I manage to do this my nose does stop bleeding, so it works. We live in a kind of world in which we need to let our hearts bleed. That will free us from a depression and nose-bleeds and all sorts of other things. It will be a sharing of blood, a kind of blood donor program. We need something of that sort.

Even if the breaking of our heart leads to our physical end, to final suffering, it will be a triumph. You may know the story – I won’t name the country because it is really a universal story – where the police herd thousands of people from a peace rally into a stadium, as a temporary prison, and the people all sing. They sing and sing and the police don’t know what to do with prisoners who sing. The leader who is playing the guitar and singing gets his hands smashed, but he keeps on singing. Then they smash his teeth so he can’t sing any more, and then they smash his head and he’s dead. And the whole stadium continues singing. Now this is the story of Christ’s death and resurrection in a contemporary version. And it’s the story of Orpheus, who was torn into pieces by furious enemies, but who was thereby distributed so that now he sings, as Rilke says, even in trees and in rocks and in lions. Everything sings. If we allow ourselves to be broken and distributed like bread then everything will become peaceful because people will eat us up and we’ll make them more peaceful. But it goes that far.

When you look at the heart of every religious tradition, you see that the starting point in each is the profound limitless sense of belonging. There is no religion in the world that would not subscribe to this.

Now, why do I say that only religion can give us the energy to pay this price? It is because I do not identify religion with religions. If I did, I couldn’t possibly say this. But there must be some relationship between religion and the religions. What is it that makes religions religious?

When you look at the heart of every religious tradition, you see that the starting point in each is the profound limitless sense of belonging. There is no religion in the world that would not subscribe to this. God does not need to be introduced here, but if you want to make this introduction, God is the reference point for that sense of belonging. Belonging comes first. It’s not out there; it’s something you experience inside, personally. And in the moments in which you personally experience that deep sense of belonging, you experience peace. Religion is peace, because that experience of limitless belonging is one of tranquility and security, and it is experienced in an attitude of non-violence. Violence makes no sense at all in that context.

It is a long way from the religious experience at the heart of every religious tradition to the religions as we find them today. But we can at least indicate the direction that way takes. First, that sense of belonging or peace is interpreted in all its different aspects, and this leads to that part of every religious tradition that is called doctrine. Secondly, that sense of universal belonging, of peace, tranquility, security and non-violence, is celebrated, and this leads to that aspect of every religious tradition that is called ritual. Then there is the willingness to live out that peace, to make it a reality, and this is morality – the commitment to living out of a sense of belonging, to realizing that peace.

The means by which we can measure how close religions come to being religious is by how truly they realize peace. Some of them limit that commitment. “Yes, we live out our belonging, but these people are the ones who belong to us on these and these conditions – and then there are all those people outside.” When these limits are no longer drawn, when the commitment to living out of that sense of belonging becomes universal, then to that extent that particular religious tradition is religious. In the course of history, religions have become more religious and then less religious, and then they reform and again become more religious. It goes up and down. We should expect that. If it happens in our own personal lives why should it not happen in the religious traditions?

Now, if we stand in a particular religious tradition, we have both the responsibility and the right to use its structures to bring about the best goals for which those structures have been set up. We can use them to bring about peace, and sometimes the structures do more than one individual can. But before we can mobilize these structures we have to make our religions religious. That is the great task for anyone who stands in any particular religious tradition.

If we understand religion in this way we can see why it can and will give us the power to pay the price of peace. If we really experience that oneness with all, that belonging to all which is the basic religious insight, then we will be able to face the fact that whatever shortcomings there are belong to all. The oneness that stands at the core of the religious experience simply eliminates “we” and “they”. And if we accept the inner authority which comes from our religious experience, then we will have the courage to rise to our responsibility.

Authority that comes from either above or below is still an authority that comes from without. The real paradigm shift is when authority comes from within.

This is where the great paradigm shift is taking place at the present moment within the religions themselves, all over the world. Authority that comes from either above or below is still an authority that comes from without. The real paradigm shift is when authority comes from within. Each of us bestows authority on all the authorities we recognize, and unless we bestow authority on them we will not recognize them as authorities. But we can also recognize, as religious language puts it, God the divine within us. This is actually the only place where we can recognize the divine: We never find it outside unless we first find it within us. We are divine; we share the divine. It is on that authority alone that we can accept other authority.

If we are one with all, then we will hurt when others hurt – and then we will be willing to give up privileges. We will be willing to pay the price. We will be able to sing to the end, and we will have the trust and courage and knowledge – deep, ingrained knowledge – that this singing will go on regardless of whether somebody smashes our teeth or our hands that play the instrument.

So finally, I would ask you to address yourselves to four questions, and to commit yourselves to what we have been talking about:

- Do you commit yourself to live from that heart of hearts where we are one with all?

- Do you commit yourself to rise to your responsibility, to go one little step at a time on the road of peace?

- Do you commit yourself to giving up as best you can complicity in exploitation?

- Do you, remembering as T.S. Eliot put it, “A condition of complete simplicity, costing not less than everything,” commit yourself to the risk of making peace happen?

If you will do all this, we are very well on the road of peace.

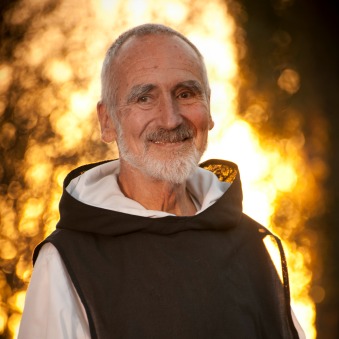

This article was excerpted from Brother David’s talk at the “Spirit of Peace” conference held in Amsterdam in March, 1985. It was originally published in the Findhorn Foundation’s One Earth magazine (pages 11-13, July/August 1985; Vol. 5, #5) with the permission of the Agape Forum for Art, who organized the conference for the benefit of the United Nations University for Peace.

Comments are now closed on this page. We invite you to join the conversation in our new community space. We hope to see you there!